Are you the person everyone tends to come to with their questions, their struggles, or their to-do lists? Whether you’re a parent, a teacher, a volunteer—or a rabbi—at some point you’ve probably wondered, “How am I supposed to do all of this?” It’s not just overwhelming; it’s the deep human realization that we were never meant to do any of this alone.

This week, we begin the book of Devarim, Moses’s parting words to the Israelites. Standing on the edge of the Promised Land, he doesn’t give a victory speech. Instead, he tells a story. Their story. He recounts the journey, the stumbles, the triumphs—and the time when he, their leader, couldn’t do it alone. “How can I bear your troubles, your burdens, and your disputes all by myself?” he asks. The answer? He appointed others. He shared leadership. He invited partnership.

This verse, and the blessing it evokes, offers a powerful blueprint for sacred community. Pirkei Avot teaches: “Do not separate yourself from the community.” This isn’t just a moral reminder—it’s a blessing. A wish that we might find our place not above or apart from one another, but within and alongside.

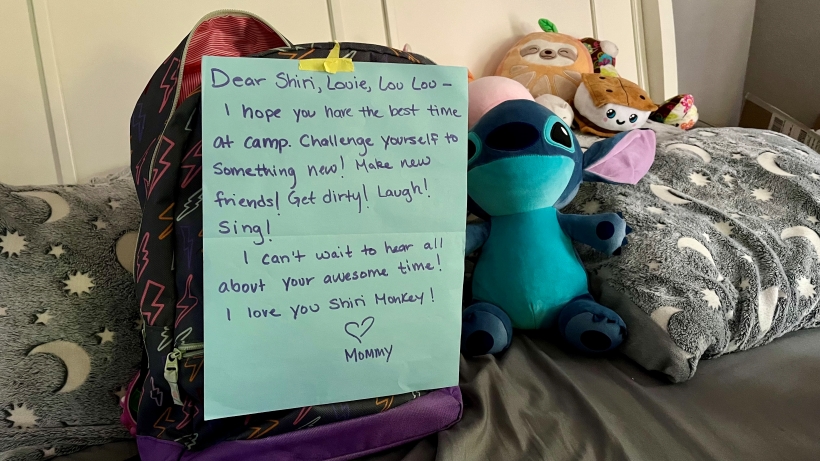

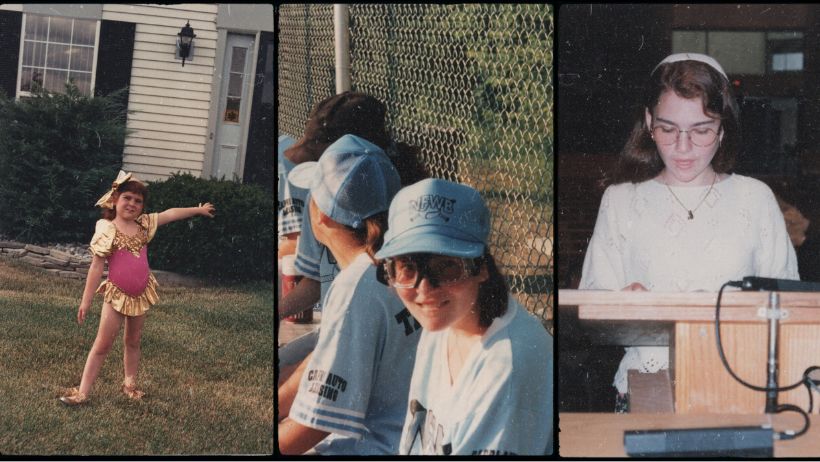

As I begin my journey as your senior rabbi, I hold this verse close. Leadership, for me, is not about bearing burdens alone. It’s about being in relationship with each other, with our sacred traditions, and with the still-unfolding story of who we are and who we’re becoming. My vision is to co-create this kehilla together: to listen deeply, dream boldly, and build collaboratively. Just as Moses realized, the future is not carried by one, but cultivated by many.

So this week, let Moses’s words remind us that holy work is shared work. Whether by showing up, offering your voice, or extending a hand, you are part of shaping this community. Let us be co-authors of our collective story. Let us not separate ourselves from the community, but draw closer, with intention, compassion, and courage. Together, may we bear not burdens, but blessings.