This is the d’var Torah I delivered at Congregation Neveh Shalom on October 18, 2025.

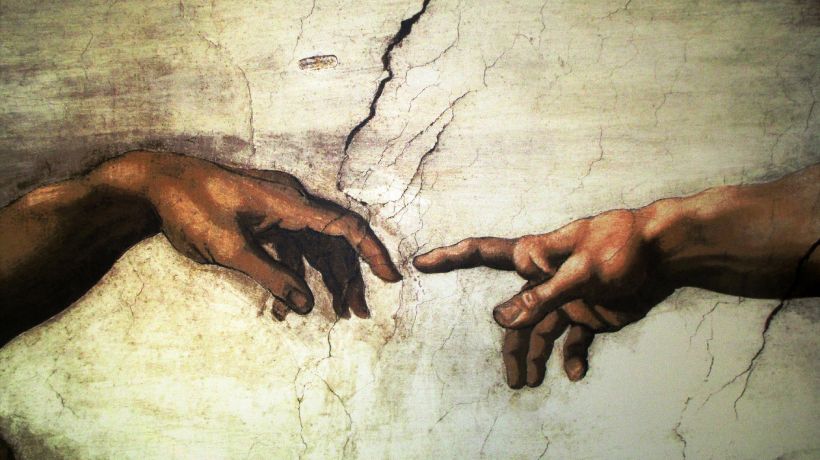

The opening chapters of Bereshit tell us that humanity is created b’tzelem Elohim—in the image of God. It’s a breathtaking statement of dignity and potential. Yet, almost immediately, we watch that potential unravel. From the first bite of the fruit to Cain’s jealousy of Abel, power is misused. The gift of being made in God’s image turns dangerous when we forget that to be like God does not mean to become God.

That tension—between creation and control, between dominion and humility—is as ancient as the Torah itself and as current as the world outside our synagogue doors.

In Bereshit, God creates a world of balance: light and dark, land and sea, rest and work. Humanity is placed in the Garden not to rule ruthlessly, but l’ovdah ul’shomrah—to serve and to protect. Yet, when Adam and Eve reach for the fruit, it is not curiosity that drives them, but the temptation of power: “You will be like God, knowing good and evil.” When Cain strikes Abel, it is again a grasping for control. From these earliest stories, Torah warns us what happens when we let power go unchecked.

Midrash Rabbah teaches: “If you corrupt the world, there is no one after you to repair it.” Power without responsibility destroys creation itself. The Torah’s first command to humanity is to name—to speak. Speech, not dominance, is our true creative act. God creates with words; we, too, are meant to build worlds through words of truth and compassion, not through control or fear.

Today, as people around the world lift their voices in the No Kings protests, that message echoes loudly. Without taking sides, we can recognize the sacred impulse behind it: a call to remember that no one—no ruler, no leader, no human—should hold unchecked power over another. The Torah’s vision of creation depends on equality, partnership, and shared responsibility.

To live b’tzelem Elohim means to wield our influence with humility—to speak truth, to protect the vulnerable, to guard creation itself. The first Shabbat in the Torah arrives when God stops creating and simply rests. Power, Torah teaches, is holy only when tempered by restraint.

May this Bereshit inspire us to build a world rooted not in control but in covenant—a world where every voice matters, and every act of creation is guided by compassion and care.